History of Quimby Country

Our History

Quimby Country, was called “The Cold Spring House” when it opened its doors to its first guests in the summer of 1893. Charles Quimby, a tinsmith and hardware store owner in West Stewartstown, NH, had leased the property from the Connecticut Valley Lumber Company, along with two other partners.

Quimby Country, was called “The Cold Spring House” when it opened its doors to its first guests in the summer of 1893. Charles Quimby, a tinsmith and hardware store owner in West Stewartstown, NH, had leased the property from the Connecticut Valley Lumber Company, along with two other partners.

At that time, the only building on the property was the Lodge, minus its current impressive chimney. The original name was chosen because of a nearby mineral spring. In fact, early pamphlets boasted that the spring’s waters were “known to be a sure cure for rheumatism, gout, kidney, and stomach trouble..” Health benefits aside, The Cold Spring House was largely promoted as a fishing camp for East Coast businessmen and politicians. And depending on which story you believe, the spring either dried up naturally in the 1950s or, in a misguided attempt to improve its flow in the 1930s, someone dropped dynamite into it sealing the vein forever.

The Lodge housed the office, kitchen, a communal living room, and a dining room, where guests sat side by side at long tables. In the first few years, guests stayed in platform tents set up near the lodge. These were not, however, spartan camping accommodations, but “high-class” tents, with wooden partitions, stoves, carpets, and furniture.

When The Cold Spring House first opened, the lake outside its doors was known as “Leech Pond.” Thankfully, it was changed to Forest Lake by act of the Vermont Legislature in 1905.

In those days, getting to The Cold Spring House was quite an ordeal. Guests rode the Grand Trunk or Boston and Maine Railroad to either Whitefield or West Stewartstown, NH, where they were met by a horse and buggy from the camp livery. In 1907, a two cylinder Cadillac joined the horses. And a wood-burning steamer, plied the waters of Big Averill Lake, bringing guests from the Norton side to the Rock. The time it took for guests to get to The Cold Spring House may explain why the average stay was a month or two.

In those days, getting to The Cold Spring House was quite an ordeal. Guests rode the Grand Trunk or Boston and Maine Railroad to either Whitefield or West Stewartstown, NH, where they were met by a horse and buggy from the camp livery. In 1907, a two cylinder Cadillac joined the horses. And a wood-burning steamer, plied the waters of Big Averill Lake, bringing guests from the Norton side to the Rock. The time it took for guests to get to The Cold Spring House may explain why the average stay was a month or two.

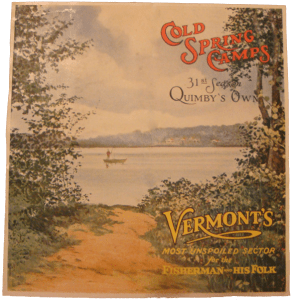

Quimby soon bought out his partners, changed the place’s name to “Cold Spring Camp,” and built nine cottages, each fully equipped with hot and cold water and indoor toilets, to make the accommodations a little less rustic. The tents remained for guests who preferred “a more out-of-door life.” At the time, those nine cottages were known by such names as Pennsylvania Cottage, Idyl-Ease, Kamp-Kill-Kare, Kamp-Kozey, Kamp Komfort, and Woodbine Camp. Today they are known as Jock Scott, Green Drake, Ginger Quill, Yellow May, Parmachene Bell, Silver Doctor, Ouananiche, and Forest Lodge. The ninth cottage, Blue Dun, ultimately burned down.

To make getting around the camp less messy, especially for ladies’ long dresses in “mud season,” Quimby built a boardwalk from the Lodge to the cottages and tents, as well as along the trail to Big Averill Lake.

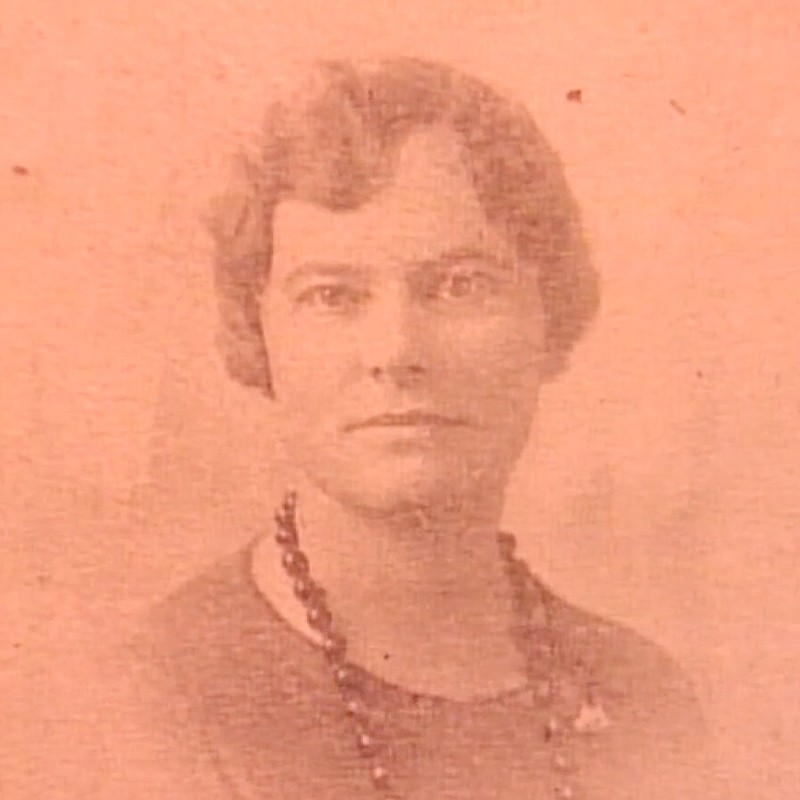

When Charles Quimby died in 1919, The Cold Spring Camp was taken over by his daughter, Hortense Adelaide Quimby. Born in 1890, Miss Quimby grew up in West Stewartstown and following high school attended State Normal School in Plymouth, NH. After graduating, she accepted a teaching position in New Jersey and briefly held the position of “social hostess” for Raymond Whitcomb Cruises. But when a teaching position opened in her hometown, she returned. And when her father died, she took over.

An attractive young woman with vibrant red hair, Miss Quimby was known to have had several suitors, but preferred to remain, in her words, “an old maid.” Her plan for Cold Spring Camp, was to transform it into a retreat for families. And she pursued that goal tirelessly.

She bought the property her father had leased, tore down the boardwalks, and began building more cottages, changing almost all their names to those of fishing flies. (Forest Lodge is the lone exception.) She added to the stables, built a clay tennis court, and began hiring counselors (Junior Hosts and Hostesses) to oversee children’s activities. Then she renamed the place Quimby’s Cold Spring Club.

Miss Quimby paid more attention to marketing than her father had. Her promotional brochures were much slicker and, although she continued to use her father’s slogan — “the only Maine camps in Vermont” — she added such claims as “No mosquitos – no blackflies,” which at least in the early part of the season is stretching the truth to the breaking point.

In addition to trying to attract families, Miss Quimby was also quite invested in maintaining the camp’s position as a mecca for fishermen. In 1925, she and one of her fishing guides started one of the first fish hatcheries in Vermont, raising salmon and trout in the “Rearing Station” on the shore of Big Averill Lake, near Sandy Beach.

In 1965, elderly and fighting bone cancer, Miss Quimby sold the Cold Spring Club to a group of long-time guests. She kept a lot on Big Averill to build a year-round home, deeding it to the Cold Spring Club’s new owners in the event of her death. Sadly, that came too soon. Miss Quimby died in St. Johnsbury, VT, in 1967. (See An Appreciation of Miss Quimby.)

This dedicated group of long standing guests kept Quimby Country open and in operation for decades under the directorship of a board. Quimby Country continued to serve families and guests under the same founding mission as established in 1893. In the fall of 2017, the board of directors decided to seek new ownership for Quimby Country to ensure its continued and longstanding success for generations to come.

Lilly and Gene Devlin purchased a majority stake in Quimby Country in February 2018. In 2021 they exercised the option to buy the remaining 49% interest in Quimby Country making them the sole owners. Lilly and Gene look forward to building on Quimby’s traditions while honoring its rich heritage and stewardship to the land and to its guests.

Click Here To See A List of Quimby Country’s Leaders from 1965- 2021

Albert Pratt

Spanning Miss Quimby’s era and that of the current owners was a slight man with a quick smile and restless energy. Albert Pratt, who worked at Quimby

Country from the 1930s until the start of the 21st century, was usually the first friendly face generations of Quimby Country guests saw as they eased their car into a parking space outside the Lodge. Alber’ (al-BEAR), as everyone called him, would invariably greet them with a wide smile and a “Welcome home, Missy.”

Albert Pratt was born in 1908 on a boat sailing from Bangor, ME, to Montreal and grew up in Richmond, ME. When he was seven, Alber’, was playing in his yard when he saw his father ride his horse into the woods. Alber’ followed and wandered into a logging area where a tree fell on him, striking his leg and head. He was hospitalized for seven months, his leg paralyzed and without feeling.

At one point, he heard the Doctor tell his mother that they would have to amputate in a few days, but that Alber’ “may not pass the night.” That night, Alber’ dreamed he went to heaven, where it was “nice and bright,” and in the morning, he had the feeling back in his leg. While regaining the use of his leg, Alber’ later attributed his difficulty learning to the accident, and he left school at the age of 12.

When he was 17, in 1926, jobs were few and far between in Canada where Alber’ had been living, so he came to Norton, VT, to look for work. He found a job at the Norton Sawmill with his brother Midi and worked there for three years, until it closed. As he was about to return to Canada, a Quimby Country fishing guide told Alber’ they were looking to hire a chore boy. Alber’ went up to Quimby Country, where he was interviewed by Miss Quimby on Friday, June 13, 1930. Miss Quimby was apparently impressed by Alber’ but afraid a “woodsman” like him might be too “tough” to work around her guests. Still, she agreed to give him a chance.

to work around her guests. Still, she agreed to give him a chance.

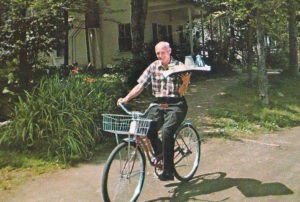

Alber’ turned that chance into the position akin to a concierge they he held for more than 70 years. He chopped wood, delivered meals and ice on his bicycle, made morning fires in cottage woodstoves, and predicted the weather. In the winter, he held a series of positions, from sawyer at an Island Pond sawmill to butler for a Quimby Country family in Englewood, NJ.

After retiring, he moved closer to his son, a race horse trainer, in Florida. That’s where he passed away, peacefully, in 2003 at the age of 95.

The sight of Alber’ steering his bike with one hand while carrying a tray above his head with the other was not just a stunt for a postcard photo. He did it – or something like it – nearly every summer day well into his 70s when someone finally convinced him to turn in his bike for a golf cart. The path he biked, or drove, between the Lodge and the very last cottage before the turn towards Forest Lake has been named in his honor “Albert’s Way.”

But Albers’ way was more than a path. It was a gentle and friendly manner. A quality of care in which everyone he met was family, and returning to Quimby Country was coming home, just as it was for him for the largest part of his life.

An Appreciation of Miss Quimby

Miss Quimby in the 1960s

High on the cold end of Vermont there once lived an exceptional woman. She had an exceptional idea and the guts to see it through.

Yes, “guts” is the right word. For Hortense Quimby lived in a time and place where men ruled, and they were as tough as the land, and the land was (and is) as tough as there is in Vermont.

Near the Canadian border in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont a little ridge separates two famous woodland lakes, Forest Lake and Big Averill Lake. Although they are less than a mile apart as the crow flies, the waters of one flow north (as Howard Mosher would say) into the Saint Lawrence and the North Atlantic, while the other drains south, down the Connecticut to Long Island Sound.

It was at the junction of these historic watersheds that Hortense Quimby by the middle of the last century had transformed what was originally a hunting camp for men into a precursor for the modern family “destination” resort. In doing so, she and her “Quimby’s” lodge became a legend of the north country. Robert Pike, who understood the north woods better than any author of his time, describes what she did in his 1959 classic Spiked Boots:

“She built the place up all alone, all the cottages and tennis courts and boats and saddle horses, without the help or encouragement of anyone. It’s hard work though. It must have near broke her heart more than once, but the tougher the sledding, the harder she pulled. She never quit.”

Miss Quimby in 1935

When Earle Newton published his history of Vermont in 1949, he singled out Quimby as “…an ardent conservationist and one of the state’s best businesswomen. (who has) developed Quimby’s into a family resort, with facilities for the care of children, and guides for the adults who find the wilderness around the Averill lakes a paradise for hunting and fishing.”

Hortense Quimby’s idea made her a pioneer in the field of destination tourism. Writing for the Vermonter magazine in 1938, Frank Howe of Bennington advised that Hortense Quimby’s resort should become “…a school for the summer business.”

Hortense Quimby was a woman of vision and strong will. She found a way to survive and make a living in a hard place by giving others the opportunity to enjoy the land she loved. A conservationist, she kept her dream on a human scale. To be at Quimby’s was to be with the Kingdom, not simply in the Kingdom.

For this great lady of the north woods carried the Kingdom where it belonged – in her heart. Today’s developers and resort planners would do well to be guided by the spirit of Hortense Quimby.

Frank Bryan, who gave this report on Vermont Public Radio, is a writer and teaches political science at the University of Vermont.